Back in June I broke the news that support for HL7s C-CDA was coming to Apple's HealthKit, giving consumers more control over their health information. This is a major step forward for patient empowerment, and also - of particular interest to me - standards-based interoperability.

But this cool new feature is meaningless if patients can't get access to their health information!

So, I'm very happy to report that today, with the launch of Apple's iOS 10, Duke Health is ready to allow patients to download their C-CDA from our Duke MyChart portal and import it into the Health app, ready for sharing with other compatible apps! This process currently requires accessing the Duke MyChart website, but we hope to add the same functionality to the MyChart iOS app in a future release.

To start, simply log into the Duke MyChart portal from the Safari browser on your iPhone or iPod touch (the iPad doesn't currently support HealthKit). Tap on the My Medical Record tab along the top, then on the Download My Record option. This will take you to a page fitting called Download your Continuity of Care Document. Simply tap the green Download button here (Note: if you choose the option to encrypt the document, you will not be able to open it in the Health app).

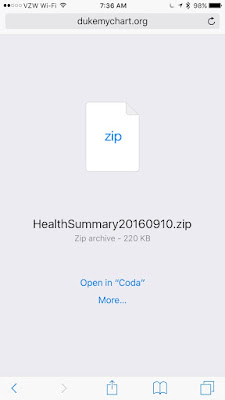

The document will then download, and you'll be presented with a screen asking you what you'd like to do with it. If it doesn't say "Open in Health," tap the "More..." button and then select "Add to Health" from the top list. It'll be the icon with the heart on a white background as shown below:

You'll then be shown a preview of the record:

Including a searchable view of the C-CDA itself (some information here redacted):

If you're happy with this information, simply tap "Save" (see left screenshot above), and the record will be imported into the Health app.

To view this record later, simply open the Health app and select Health Records, where you will be able to view all imported records:

If you tap on the individual record from here, you will be able to view it as well as share it with other apps that can accept C-CDAs.

Also note that you are not prevented from importing documents from other individuals. I was able to import my daughters' C-CDAs and view them all from the Health app.

As I've mentioned previously, on import into the Health app there is very little parsing going on - just enough to identify the individual. If you share this document with another app, it will need to handle document parsing itself in order to make use of the structured content. Fortunately, there are already some open source tools popping up to handle such tasks, such as this one written by Alex Nolasco as part of HL7's C-CDA Rendering Tool Challenge, which contains a C-CDA parser as well as an iOS viewer written in Objective-C.

This is a great step forward in our march towards greater patient empowerment and health system transparency. I can't wait to see where the next steps take us!

But this cool new feature is meaningless if patients can't get access to their health information!

So, I'm very happy to report that today, with the launch of Apple's iOS 10, Duke Health is ready to allow patients to download their C-CDA from our Duke MyChart portal and import it into the Health app, ready for sharing with other compatible apps! This process currently requires accessing the Duke MyChart website, but we hope to add the same functionality to the MyChart iOS app in a future release.

To start, simply log into the Duke MyChart portal from the Safari browser on your iPhone or iPod touch (the iPad doesn't currently support HealthKit). Tap on the My Medical Record tab along the top, then on the Download My Record option. This will take you to a page fitting called Download your Continuity of Care Document. Simply tap the green Download button here (Note: if you choose the option to encrypt the document, you will not be able to open it in the Health app).

The document will then download, and you'll be presented with a screen asking you what you'd like to do with it. If it doesn't say "Open in Health," tap the "More..." button and then select "Add to Health" from the top list. It'll be the icon with the heart on a white background as shown below:

You'll then be shown a preview of the record:

Including a searchable view of the C-CDA itself (some information here redacted):

If you're happy with this information, simply tap "Save" (see left screenshot above), and the record will be imported into the Health app.

To view this record later, simply open the Health app and select Health Records, where you will be able to view all imported records:

If you tap on the individual record from here, you will be able to view it as well as share it with other apps that can accept C-CDAs.

Also note that you are not prevented from importing documents from other individuals. I was able to import my daughters' C-CDAs and view them all from the Health app.

As I've mentioned previously, on import into the Health app there is very little parsing going on - just enough to identify the individual. If you share this document with another app, it will need to handle document parsing itself in order to make use of the structured content. Fortunately, there are already some open source tools popping up to handle such tasks, such as this one written by Alex Nolasco as part of HL7's C-CDA Rendering Tool Challenge, which contains a C-CDA parser as well as an iOS viewer written in Objective-C.

This is a great step forward in our march towards greater patient empowerment and health system transparency. I can't wait to see where the next steps take us!